2022 Drought Offers Valuable Lessons

A dry late summer into fall of 2022 had many Midwest corn growers concerned about the drought. More than half of the farmers surveyed in August by Pioneer said they were dealing with moderate to severe drought stress.

“Last summer, coming out of a second consecutive year of La Niña, a predicted drought was already in place across much of the nation’s midsection, especially west of the Mississippi River,” says Brad Rippey, USDA Meteorologist. “I credit the National Weather Service forecasters for nailing the long-range forecast last summer—where the eastern Corn Belt fared reasonably well, and the Northern and High Plains had a tough year with drought and heat combining to really take a toll on crops.”

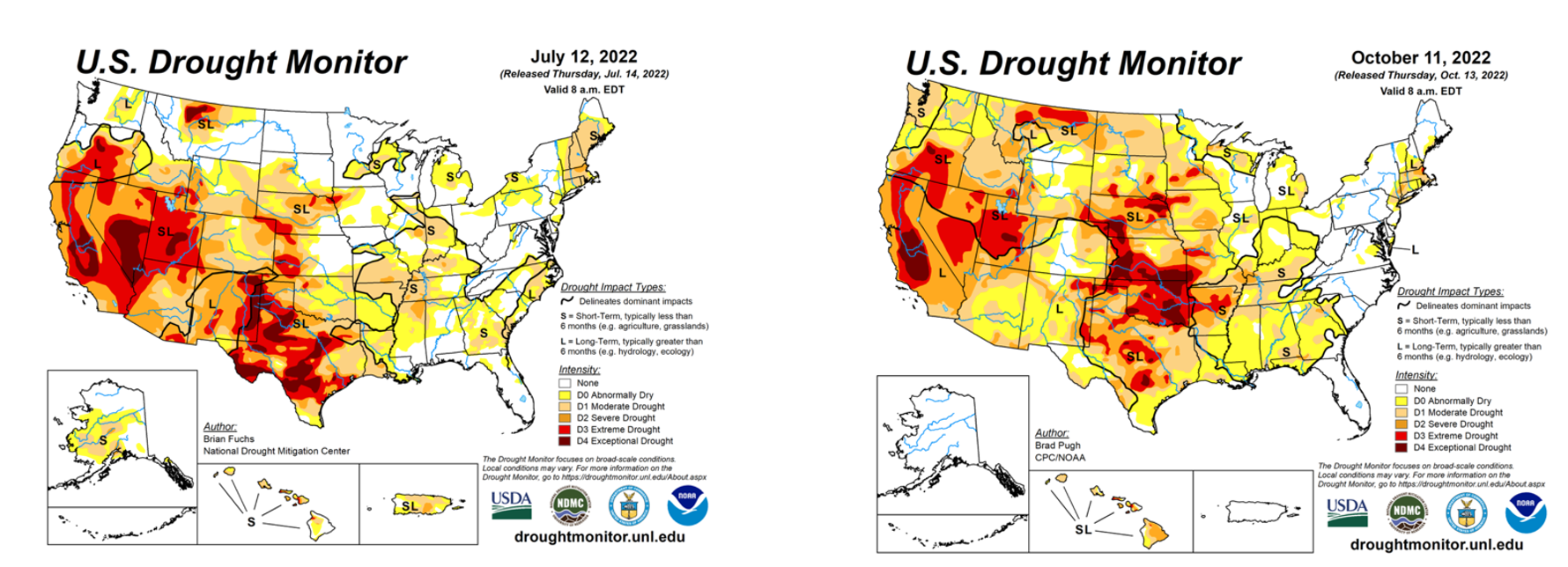

These two snapshots of drought severity (July and October) show the drought marching eastward toward the end of the growing season. The percentage of U.S. corn production area in drought was 17% in mid-June, 31% in early August and climbed to 71% in late October. “Yields would have been drastically reduced if that peak percentage happened in July,” Rippey says.

The highest-producing corn states mostly survived without drought during critical flowering and pollination time, leading to decent average yields in Iowa (202 bu./A) and Illinois (215 bu./A). “But the western Corn Belt up into the northern Plains suffered under drought and heat, as yields in Nebraska were down 13% and Kansas dropped 17% compared to 2021,” he adds. “The lack of excessive heat during pollination this summer—from Iowa through the eastern Corn Belt states—played a critical role in keeping yields higher.”

Many farm families vividly recollect severe crop-killing droughts in 1988 and 2012. Even more farmers and ranchers have witnessed the economic impact of flash droughts, excessive heatwaves, flooding, derechos and blizzards that can steal income and bushels overnight. And these extreme weather events now occur more frequently. A quick internet search of “billion-dollar disasters” in the U.S. shows proof of 338 weather and climate events that exceeded a billion dollars since 1980. 2022 produced 18 such events.

“Climate change is indeed contributing to a more meandering jet stream that can lock into unusual loops and bends that bring flooding, drought, heat and cold—sometimes in different areas simultaneously,” Rippey says.

While the average rainfall and snowfall amounts haven’t changed significantly, the number of extreme events has increased. “We have longer dry stretches between events, and we also have higher intensity precipitation quite often leading to more runoff and less percolation into soils,” he adds.

Jeff Coulter, University of Minnesota Extension agronomist, has witnessed significant weather extremes over the last two years. From extreme early-season drought and excessive heat in 2021 followed by substantial rainfall differences in 2022, he sees farmers adopting certain practices that can help reduce drought risks:

Rippey suggests farmers track the increasing frequency of more adverse weather extremes and monitor current drought conditions. “American farmers and ranchers are incredibly adaptive to changing climate and other factors that impact their business. The National Weather Service’s science of forecasting has also come a long way in identifying general climate trends—like those shown in the monthly and seasonal drought outlooks—that can help farmers improve decisions,” he says.

Content provided by DTN/Progressive Farmer.

Find expert insights on agronomics, crop protection, farm operations and more.