If a good crop of winter annual weeds often takes root in your fields, you're in good company. When harvest is wet, growers are able to make fewer fall herbicide applications.

If a good crop of winter annual weeds often takes root in your fields, you're in good company. When harvest is wet, growers are able to make fewer fall herbicide applications.

For corn fields, rotated from soybeans, watch for herbicide-resistant marestail (horseweed), field pennycress, henbit, downy brome, chickweed, mustards, prickly lettuce, shepherd’s purse, dandelion and more, depending on your area. If your field is no-till, weed species and weed size may vary. Some no-tillers are reducing weed issues with a good spring cover crop.

Early burndown control saves yield

To reduce the impact of winter annual weeds (and early spring weeds) on early corn growth, make burndown applications of residual herbicides before planting. (Keep in mind burndown herbicides and residual herbicides are not always the same.) This helps achieve a clean field prior to seeding, as these weeds that are flowering or showing stem elongation are more difficult to control while consuming soil moisture.

Late winter annual weed control also increases nitrogen uptake by growing weeds. A 2010-2011 eastern Kansas trial by Kansas State University showed that delaying weed control until near the time of corn planting reduced corn population by 526 plants/acre, reduced corn N uptake by 24%, and cut corn yields by 7.6 bushels/acre—compared to herbicide application in March or the previous November.

Five out of six site years saw yield loss from delayed weed control in a University of Nebraska study. Not controlling winter annual weeds saw yields drop more than 5%, and up to 10% in four of the six site years. The critical dates for winter annual weed control to prevent yield loss ranged from April 15 to May 5 for corn.

Pay attention to product labels

According to Meaghan Anderson, Iowa State University field agronomist, herbicide treatments made on sunny days with warm daytime temperatures above 55 degrees F and night temperatures above 40 degrees F will be more successful than cooler conditions. Increasing herbicide rates may be necessary if weeds are larger in colder conditions.

“Effective burndown treatments should follow herbicide label suggestions for carrier type, carrier volume, nozzle type and environmental considerations,” she says. “When selecting burndown treatments, consider the likelihood of resistant horseweed (marestail) biotypes in the field. Group 9 (glyphosate) and Group 2 (ALS) resistant populations are widespread across Iowa. Including 0.5 lb. a.e. 2,4-D LVE, 0.25-0.5 lb. a.e. dicamba (Group 4) or a saflufenacil product (Group 14) to glyphosate will increase the consistency of horseweed control, even in fields without glyphosate resistance.”

Anderson recommends to always check pesticide labels for planting restrictions. Most 2,4-D labels have a 7- to 14-day planting restriction for corn following a 2,4-D application. Ester formulations of 2,4-D allow for a shorter interval to crop planting than amine formulations. In addition, esters often perform better under the cool conditions commonly encountered with spring applications.

Herbicide resistance

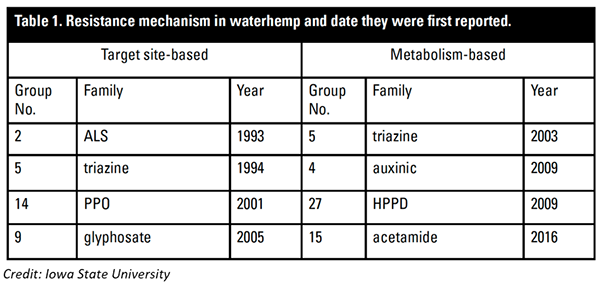

University of Illinois weed scientist Aaron Hager knows 2020 will be an even larger challenge with herbicide-resistant weeds. “Many Illinois producers have experienced resistance caused by a modification of the herbicide-binding site (known as target-site resistance), whereas fewer producers have dealt with instances where herbicide resistance results from enhanced herbicide metabolism,” he says. “Many weed scientists consider metabolic herbicide resistance as the next frontier of challenge for successful crop production.”

Hager and his colleagues announced a finding last year of waterhemp with Group 15 resistance (which includes acetochlor, dimethenamid, pyroxasulfone, and metolachlor). Such rapid metabolism by the weed is the same mechanism used by corn plants to survive Group 15 herbicides. This announcement was followed by reports of 2,4-D resistance in waterhemp in Illinois, Nebraska, and Missouri, (each of these states reported 2,4-D resistance prior to confirmation of Group 15 resistance) and in Palmer Amaranth in Arkansas and Kansas. And the Kansas Palmer amaranth population was also resistant to dicamba. All these cases are believed to be due to the weeds’ enhanced ability to degrade the herbicides.

Metabolism-based resistance (MBR) is different from target-site resistance (most common for Group 1, 2, 5 and 14 herbicides). MBR is non-target site resistance, which allows the herbicide to be detoxified before reaching the target site—posing unique threats compared to other resistance mechanisms.

Bottom line, it’s critical to develop herbicide programs that rely on multiple effective herbicides to provide full-season control to reduce the weed seed bank.

Content provided by DTN/The Progressive Farmer

The More You Grow

Find expert insights on agronomics, crop protection, farm operations and more.